Author: Antoni Seuren

By 2016, 30% of households in the Netherlands were in debt (CBS 2017). But what does this mean? Household debt can be understood as the combination of consumer debt and mortgage loans owed by a single household.

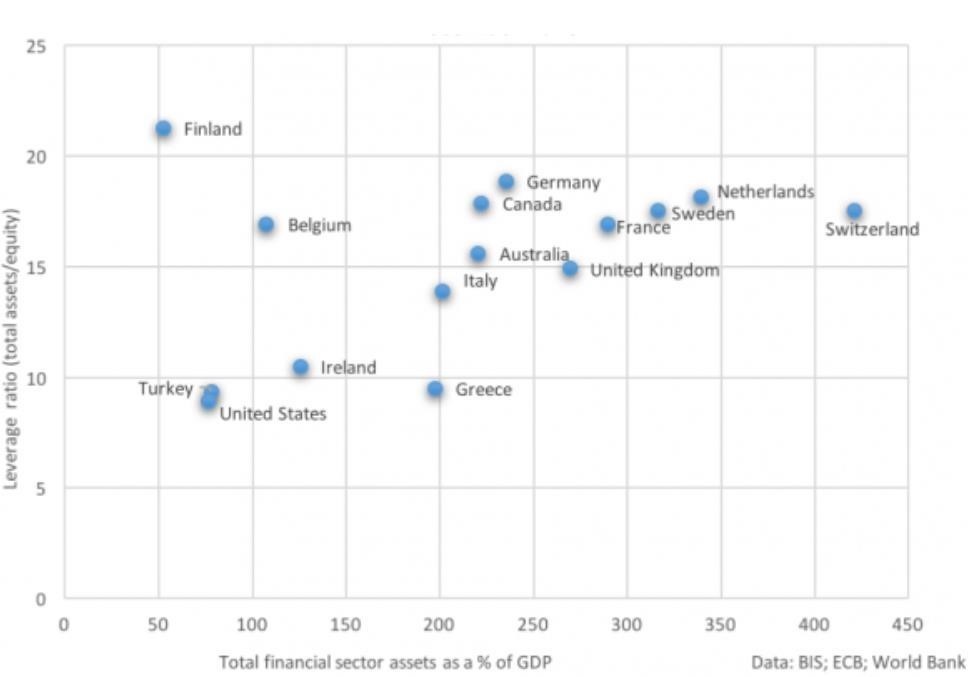

Figure 1. National Financial Sectors of 15 OECD Economies: Leverage and Relative Size (Mulder 2018)

Figure 1. National Financial Sectors of 15 OECD Economies: Leverage and Relative Size (Mulder 2018)‘Household debt’ is an umbrella term used to describe the combined debt owed by a household; both ‘good’ debt and ‘bad’ debt (Smith 2020). Bad debt is defined as debt that derives no financial long-term benefit and often form from credit card debt to consumer debt (Smith 2020). The idea of bad debt is that the purchased item or good maintains a depreciating value over time. Within the Netherlands, the issue of bad debt is not as prominent as good debt, accounting for 1/10 of indebted household cases (CBS 2017).

Good Debt

Good debt is defined as incurred debt whereby the short-term loss is smaller than the long-term gain from incurring debt (Haverkamp 2019). An example of good debt would be a house mortgage. A mortgage is a deal signed between 3 parties: the house seller, the bank and the house buyer (Parker 2020). The house seller would sell the house to the house buyer, with the house buyer using the banks money. Prior to this however, the house buyer must negotiate a deal with the bank on how they will pay back what was borrowed, at what interest and over how much time. Thus, ownership of the house is granted to the house buyer on condition that they pay back their mortgage loan within the agreed time (Parker 2020).

This is an example of good debt as in paying back the loan it in debts the house buyer for this time period (Haverkamp 2019). Once the mortgage is complete, the house is completely owned by the house buyer. The house now adds value to the house buyer’s asset wealth. Mortgage debt is the most prominent form of debt reflected in the vast majority of indebted households in the Netherlands (Mulder 2018). This is because interest rates on mortgages are currently at an all-time low.

Furthermore, it is interesting that the large majority of households in debt are middle-income households headed by young people below the age of 33 (OECD 2017). Within this majority, many households consists of people who pursued education after high school (OECD 2017). Why is it then that highly educated youth pursue mortgage loans and choose to take on debt?

Benefits of Mortgage Debt:

- Low interest (burden of high interest is removed, mortgage loan paid back is variably little more than the value of the property).

- Tax benefits (see below):

- Impact of Increasing Income Tax: Since 2016, income tax has increased for low and middle-income households (Belastingdiesnt 2019). Of those who maintain mortgage debt, the large variety fall within middle-income households, thus pay 42% tax (OECD 2017). The incentive for young household owners to spend (e.g. on mortgage) as opposed to save, has grown as a result of increased taxes.

- Impact of Mortgage Tax Break: Moreover, the government has provided a tax-refund scheme. The scheme implies that tax is deductible up to 49% of the mortgage interest paid monthly (IamExpat 2019). As a result, the derived benefits and long-term gain make the cost much lower in comparison to renting.

Risks of Mortgage Debt (for the Individual):

- Increased interests on mortgage for the individual (for example, if a person could not pay the mortgage for a period of 3 months because they were transitioning jobs, the agreed time period to pay the loan back will elapse by 3 months. Once this has occurred, the lender maintains right to increase interest for the remaining payments (SNS 2020).

- May lose ownership rights (for example, if a person could not pay the mortgage for a prolonged period of time, say, 2 years, the lender can foreclose and cease possession of the property. In some cases, the individual can receive part of the previously paid loan, in other cases the individual may not. This is largely dependent on how large the down payment on the property was (e.g. small down payment carries more risk for bank) (SNS 2020).

- Penalization on credit rating: Should a person be unable to pay back their mortgage loan, it will become increasingly difficult to acquire any other form of credit. This in turn will create a credit-trap which makes it increasingly easier for an individual to fall into debt, only now they have limited options (IamExpat 2019). A severe credit-trap may make future purchases, like cars, near impossible. It then becomes more difficult to build a wealth and assets portfolio (IamExpat 2019).

Risks of Mortgage Debt (for Society):

As mentioned, close to 1/3 of Dutch households are indebted largely because of mortgages. This means the risk of households defaulting on their mortgages carries risk that impacts 1/3 of society. Such a rippling effect carries macro-economic consequences as well (Hands on Banking 2019). Risks include:

- Over-borrowing effect: when too many households over-borrow (e.g. borrow more than they are able to pay back) the risk of these households defaulting is significant (Hands on Banking 2019). This becomes consequential as it implicates the lender (banks) and the house buyers. The financial industry is a significant sector within the Netherlands (SCP 2019). So, if households are unable to pay back loans it directly affects the financial sector (Klein 2019). More worryingly, it also implicates all other sectors the financial sector finances. This effect is what caused the Financial Crisis in 2008.

- Credit-trap effect: If the vast majority of indebted households fall within the credit-trap, economic and social mobility is reduced (Ghiaie 2018). Consequently, more households risk falling into poverty (Ghiaie 2018). All these effects interact to decrease economic productivity, further implicating everyone in society and not just those directly involved (Ghiaie 2018).

Clearly, good debt can become bad. It is crucial that all governments, not just that of the Netherlands, account for the risks of nation-wide mortgage scheme and what they imply. It is a financial resource that can both make an economy (improving general wealth), or break an economy (macro-economic risks).

References:

Belastingdienst (2019). “Tarieven voor personen die de AOW-leeftijd nog niet hebben bereikt.” Belastingdienst. At https://www.belastingdienst.nl/wps/wcm/connect/bldcontentnl/belastingdienst/prive/werk_en_inkomen/bijzondere_situaties/middeling_sterk_wisselende_inkomens/belastingteruggaaf_berekenen/u_bent_het_hele_middelingstijdvak_jonger_dan_de_aow_leeftijd/tarieven_voor_personen_die_de_aow_leeftijd_nog_niet_hebben_bereikt.

CBS (2017). “Trends in the Netherlands 2017.” (2019). CBS. At https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/_pdf/2017/44/trends_in_the_netherlands_2017_web.pdf.

Ghiaie, H. (2018). “Macroeconomic Consequences of Bank’s Assets Reallocation After Mortgage Defaults,” THEMA Working Papers 2018-12, THEMA (THéorie Economique, Modélisation et Applications), Université de Cergy-Pontoise.

Hands on Banking (2019). “The Benefits and Risks.” Hands on Banking. At https://handsonbanking.org/adults/using-credit-advantage/credit/the-benefits-and-risks-of-credit/.

Haverkamp, K. (2019). “Mortgages: The difference between Good Debt vs. Bad Debt.” Mortgage Loan. At https://www.mortgageloan.com/mortgages-difference-between-good-debt-vs-bad-debt.

IamExpat (2019). “Dutch Mortgages: Fees, Additional Costs & Tax Relief.” IamExpat. At https://www.iamexpat.nl/housing/dutch-mortgages/fees-costs-tax-relief-netherlands.

Klein, M.C. (2019). “Why is the Netherlands Doing so Badly?” Financial Times. At https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/06/16/2166258/why-is-the-netherlands-doing-so-badly/

Mulder, N. (2018). “A New Dutch Disease? Private Debt in the Netherlands.” Private Debt Project. At https://privatedebtproject.org/view-articles.php?A-New-Dutch-Disease-Private-Debt-inthe-Netherlands-22.

OECD (2017). “Understanding the Socio-Economic Divide in Europe.” OECD. At https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/cope-divide-europe-2017-background-report.pdf.

Parker, L. (2020). “How Mortgages Work – a Step-by-Step Guide.” London and Country. At https://www.landc.co.uk/mortgage-guides/how-mortgages-work-a-step-by-step-guide/.

Smith, L. (2020). “Good Debt vs. Bad Debt: What’s the Difference?” Investopedia. At https://www.investopedia.com/articles/pf/12/good-debt-bad-debt.asp.

SCP (2019). Facts and Figures of the Netherlands. The Netherlands: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

SNS (2020). “A mortgage in The Netherlands.” SNS Bank. At https://www.snsbank.nl/particulier/hypotheken/mortgage-in-the-netherlands.html.