Author: Antonia Pieper

The word “addiction” comes from the Latin term for “enslaved by” or “bound to” – and anyone who has struggled with overcoming an addiction, or has tried to help someone with doing so, can understand why.

Addiction is often defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder which affects the functioning of the brain and body (NIH 2018). It manifests in three distinct ways: craving the object of addiction, losing control over its use, and continuing to seek it despite adverse consequences (NIH 2018). In this way, addiction not only upsets the individual, but instead spreads its damage throughout their wider social network, affecting families, relationships and even schools or workplaces.

The Different Faces of Addiction

Today, most experts generally recognize two types of addiction, namely behavioral and chemical addiction. Behavioral addiction refers to persistent, compulsive patterns of action such as excessively shopping, playing video games or gambling. Chemical addiction on the other hand involves the use of addictive substances like alcohol, nicotine or opioids (Raypole 2020).

Both types of addiction can be equally damaging however. Common symptoms include intense, overwhelming cravings for the object of addiction, spending less time on previously enjoyable activities, as well as severe bouts of anxiety, depression or other withdrawal symptoms when attempting to quit (Raypole 2020).

The Pleasure Principle

What drives individuals into addiction in the first place however? Why is it so difficult to break away from the object of addiction even when its negative consequences become destructive? One answer to these questions lies in the chemistry of the human brain.

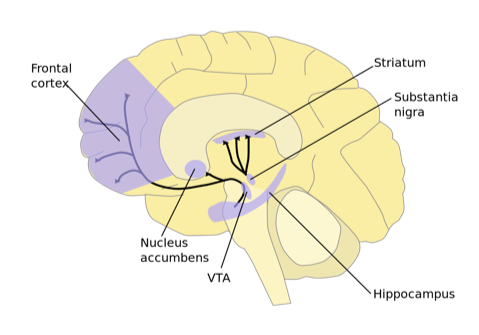

The brain registers all pleasures in the same way, whether they come from a psychoactive drug, a sexual encounter, a monetary reward of a satisfying meal. In the brain, pleasure leaves a distinct signature: the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the “nucleus accumbens,” a bundle of nerve cells clustered underneath the cerebral cortex. This region is also called the brain’s “pleasure center” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Brain’s Reward Center

Figure 1. The Brain’s Reward CenterAll objects of addiction – from gambling to nicotine to heroin – cause a powerful rush of dopamine to the pleasure center. The probability that a pattern of behavior or the use of a drug will lead to addiction is linked to three conditions: the speed with which it promotes dopamine release, the intensity of that release, as well as its reliability.

Methamphetamine (MA) for example, is considered a highly addictive drug for these exact reasons. First, MA has a relatively high lipid solubility, meaning that it dissolves quickly within bodily fats and oils. This feature allows the drug to be transferred rapidly across the blood-brain barrier and subsequently release dopamine into the brain’s pleasure center at high speed (Barr et. al. 2006).

Second, MA promotes an extremely intense release of dopamine and therefore of feelings of satisfaction. A study found that within 30 minutes of intake, dopamine levels had skyrocketed by 1350% compared to the baseline. Even almost three hours later, these levels were still up by close to 500% (Panenka et. al. 2013).

Finally, the behavioral and psychological effects of MA last much longer than other drugs, while at the same time remaining very consistent even over prolonged use. On average, a “trip” on MA will last around 8 to 13 hours, compared to about 1 to 3 hours for cocaine for example (Barr et. al. 2006). Combined, these characteristics – speed, intensity and reliability – make MA a highly dangerous and addictive drug.

The Bottom Line

Objects of addiction – be they behavioral or chemical – provide a shortcut to the brain’s reward system by flooding the pleasure center with dopamine quickly and with minimal effort from the individual. The hippocampus consequently remembers this instant sense of satisfaction. In this way, the brain begins to prioritize this “easy fix” over other sources of pleasure, ultimately driving you to go after it over and over again (Harvard Health 2019).

References:

Barr, Alasdair M., William J. Panenka, G. William MacEwan, Allen E. Thornton, Donna J. Lang, William G. Honer and Tania Lecomte (2006). “The need for speed: an update on methamphetamine addiction.” Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 31(5): 301-313.

Harvard Health (2019). “Understanding Addiction.” Help Guide. At https://www.helpguide.org/harvard/how-addiction-hijacks-the-brain.htm

NIH (2018). “Drugs, Brains and Behavior.” National Institute on Drug Abuse. At https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drug-misuse-addiction#footnote.

Panenka, William J., Ric M. Procshyn, Tania Lecomte, G. William MacEwan, Sean W. Flynn, William G. Honer and Alasdair M. Barr (2013). “Methamphetamine use: A comprehensive review of molecular, preclinical and clinical findings.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 129(3): 167-179.

Raypole, Crystal (2020). “Types of Addiction and How They’re Treated.” Healthline. At https://www.healthline.com/health/types-of-addiction.